Congo, Christianity, & Colonialism: I finally finished The Poisonwood Bible

It took me almost three years to finish reading the novel, The Poisonwood Bible by Barbara Kingsolver, and, trust me, I have a lot to say! So much so that I am dedicating a full blog post about it! And I hope to capture all my thoughts precisely.

The novel is about a missionary family: Nathan Price, the Baptist evangelical, his wife, and his four young daughters, who go to the Belgian Congo in 1959 to bring the Gospel to the Congolese people—and show them “the way.” They arrive in the fictional village called “Kilanga” and are unprepared for “the village life in the jungle”. According to the missionary family, the Congolese people are uncivilized and ignorant, and so on. The book covers three decades in the Congo.

My overall criticism/thoughts

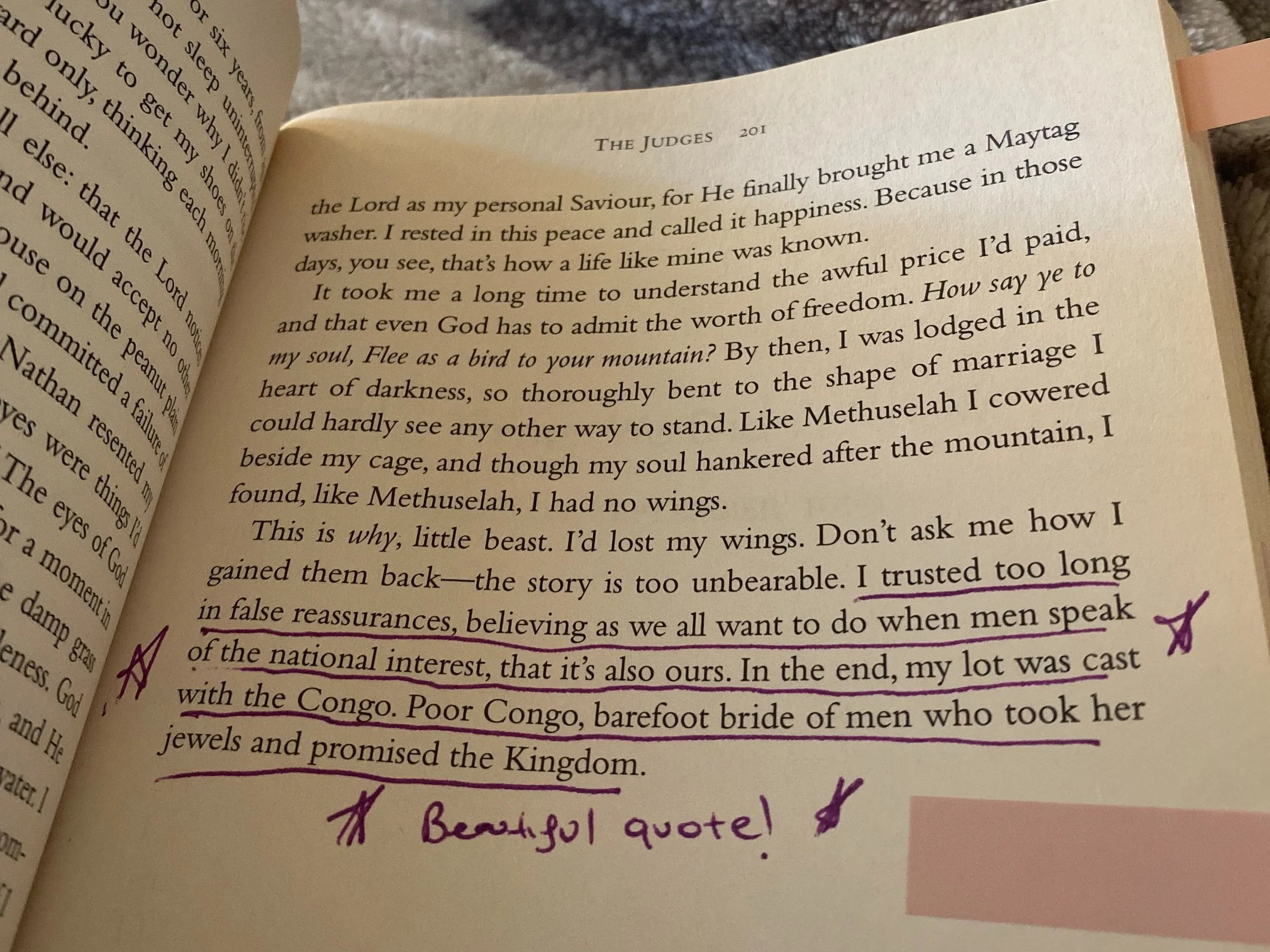

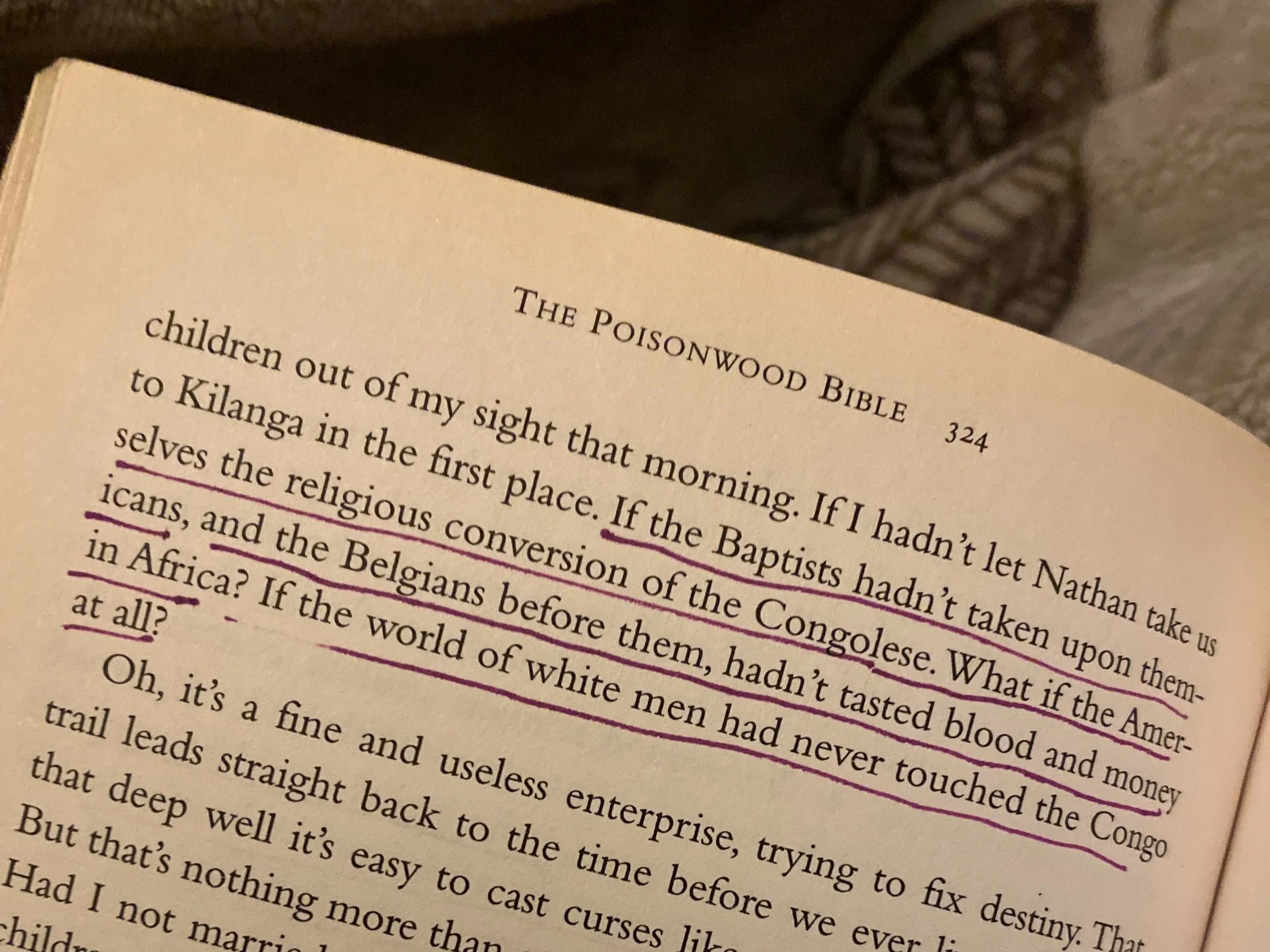

All in all, I do appreciate the way the author wrote about the history of Congo in such depth: covering colonialism and post, missionaries in the Congo, political situations, etc. I highlighted so much—So many great sentences/quotes!

“Now everyone’s pretending to set the record straight: they’ll have their hearings, while Mobutu makes a show of changing all European-sounding place names to indigenous ones, to rid us of the sound of foreign domination. And what will change? He’ll go on falling over his feet to make deals with the Americans, who still control all our cobalt and diamond mines. In return, every grant of foreign aid goes straight to Mobutu himself.”

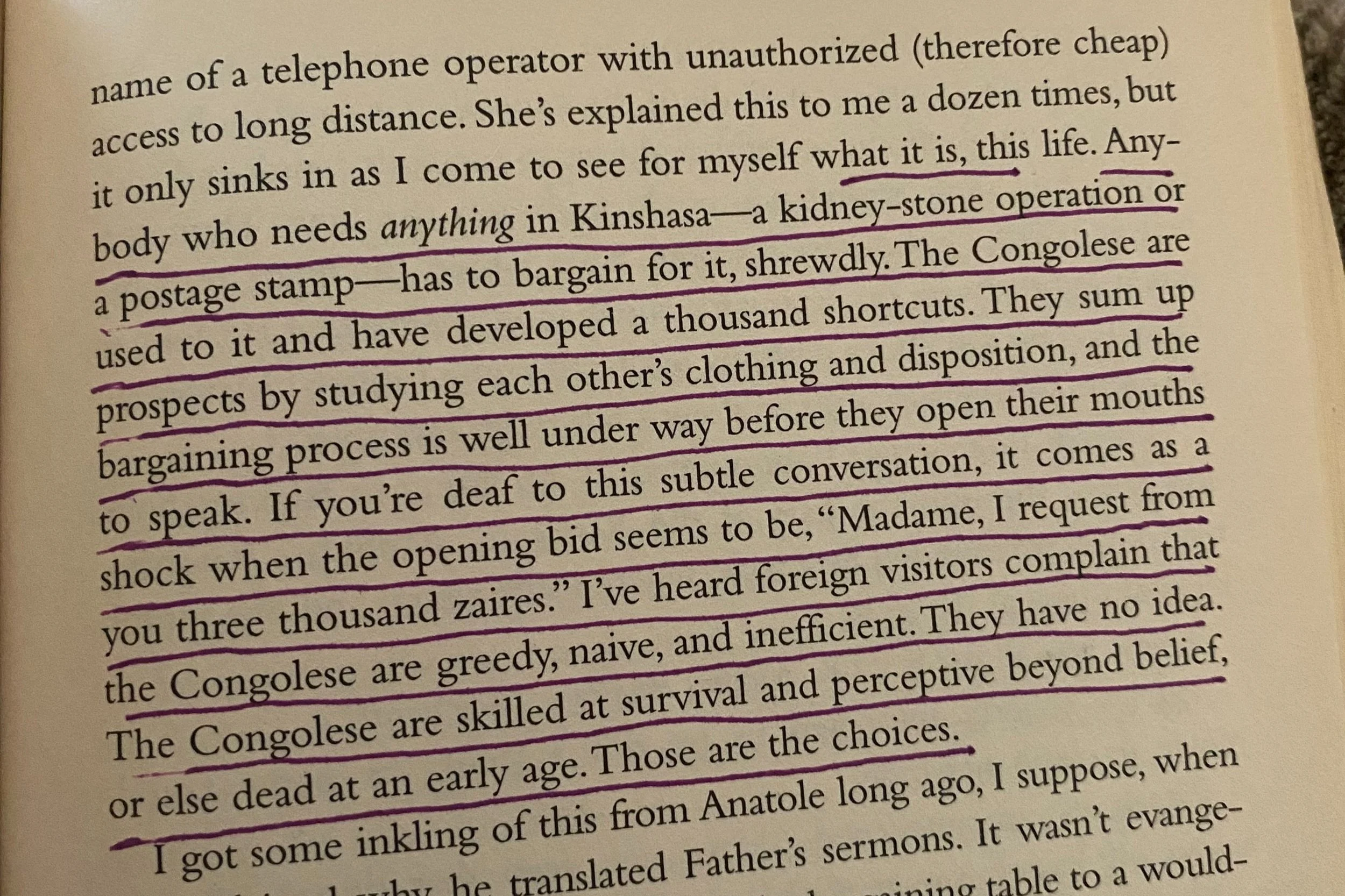

There was a lot of truth regarding the ugly politics in the Congo or cultural observations. Sadly, the political situation hasn’t changed much, even the Congolese people's mentality regarding the survival mindset, i.e: bribing etc! So accurate, and it pains me to write this, as someone with Congolese roots. This is why I wanted to write this review from the point of view of someone who loves reading fiction and happens to have ties to Congo.

“The same argument is made by telephone operators, who’ll place a call outside the country for you only after you specify the location in Kinshasa where you’ll leave l’enveloppe containing your bribe. Same goes for the men who handle visas and passports. To an outsider it looks like chaos. It isn’t. It’s negotiation, infinitely ordered and endless.”

“She’s explained this to me a dozen times, but it only sinks in as I come to see for myself what it is, this life. Anybody who needs anything in Kinshasa—a kidney-stone operation or a postage stamp—has to bargain for it, shrewdly. The Congolese are used to it and have developed a thousand shortcuts. They sum up prospects by studying each other’s clothing and disposition, and the bargaining process is well under way before they open their mouths to speak. If you’re deaf to this subtle conversation, it comes as a shock when the opening bid seems to be, “Madame, I request from you three thousand zaires.” I’ve heard foreign visitors complain that the Congolese are greedy, naive, and inefficient. They have no idea. The Congolese are skilled at survival and perceptive beyond belief, or else dead at an early age. Those are the choices.”

Christianity in Congo

I know firsthand the stronghold that missionaries and Christianity have had (still have) in the Congo. However, the author downplayed it a bit. In the Kilanga village at least, it seems that most people rejected the Gospel, according to the author. But she missed the opportunity to write about how the Gospel was widely accepted before & during Mobutu’s regime—and is still the most respected and popular religion in Congo. Congolese have since been brainwashed into “waiting” for Jesus to change the nation—without action—while “foreigners” continue to loot natural resources (Yes, the political situation is more complex than that: The Belgium government and American government played a big role in it as well—and Congo’s very own greedy leaders—but the focus of this section is religion). Side note, I write a bit about this in my own work.

“Like a princess in a story, Congo was born too rich for her own good, and attracted attention far and wide from men who desire to rob her blind. The United States has now become the husband of Zaire’s economy, and not a very nice one. Exploitive and condescending, in the name of steering her clear of the moral decline inevitable to her nature.”

Regarding Nathan Price, the Missionary who brought the Gospel to the “villagers” in the book—he was obsessed with baptizing children and shoving the bible down everyone’s throat. He was very intense and manipulative—to the point that it resulted in an unfortunate tragedy (No spoiler). As we know, many Baptist missionaries tried to convert Congolese or Africans in general to Christianity and encouraged them to leave behind their traditions, witch doctors, and“fetishes.” But the book made it seem as if Nathan Price wasn’t successful at all—in his mission—when I know firsthand how Christianity was indeed accepted as the “main” religion in Congo. Nathan Price’s character was so extreme towards the end that it was hard to believe it, unfortunately. Almost comical.

Unrealistic Scenario during the Congo Crisis/Revolution- Post-colonialism

One thing that bothered me was how unrealistic things in the Congo were portrayed at times. For example, a white mother leaving her daughters behind in the Congo during a very crazy time—1961/1962! Alone! During the “Independence Movement” and after Lumumba was killed, most whites were practically chased out or worse. It is too difficult to imagine a minor (Leah) would have been left behind—in an African village! And she was sick? Okay, yes she had Anatole (her male Congolese friend/boyfriend) but the whole situation was just unrealistic, given how crazy things were during this period (I wasn’t there, obviously, but from what I know).

I want to be oppressed vibes!

In the years to come, after deciding to stay in the Congo with her boyfriend/husband, Leah, one of the daughters, went on and on about how she was poor, hungry, and miserable—even though she had the option to leave the Congo and have a better life. It is hard to believe her husband would stay in those circumstances WITH CHILDREN when they had the option for a better life—for their kids. It irritated me so much because this is what you call self-inflicted suffering.

It is so obvious that this was written with the mindset/mentality of a white woman trying to speak for Congolese people. I appreciated Leah’s desire to fight for justice or hope for true freedom or independence for Congo, but at times it screamed: “I want to be oppressed.” Leah and Anatole had the chance to start fresh in the US, but they went back to Congo during Mobutu’s regime! When Anatole was a wanted man for being pro-Lumumba? That is so laughable! Congolese were doing the total opposite during that time—no matter how much of a pro-Lumumba activist they may have been, they were fleeing! Therefore, it is so unrealistic for Leah and Anatole to choose not to stay in America because people were criticizing the scars on her husband’s face or because they had a hard time adjusting to life in the US. Ask any immigrant who has *truly* suffered: that is a minor disadvantage—especially then! Congolese were fleeing with no return!

But I guess the author had to do it for the plot. Or else, how would we know and see Leah’s character arc in the Congo?

The oldest sister was an open racist, but the most entertaining character.

From the beginning, Rachel wanted to leave Africa so badly, but now years later (70s/Mobutu regime), she conveniently inherited her late husband’s hotel in Brazzaville and is so suddenly happy to stay. For so long? I didn’t buy it. Because most “foreigners” eventually left, even for just a break, and then maybe returned. So here you have a white (single) American woman in her 40s/50s, running a hotel in Brazzaville during a very turmoil time in the history of Congo—and never ever leaving the continent—it was too hard to believe.

Lastly, in the end, 20-something years later, the mother and daughters return to the continent and the narrator mentions that this was during the African War.

“In the six months since they began to plan their trip, the Congo has been swept by war.”

I am laughing again because, once again, this family conveniently and comfortably seems to be in the Congo during its most traumatic times—during another crisis: the war. They are somehow not afraid of being in danger and feel confident that they can just find their old little village of Kilanga when the country is torn apart?? Maybe I missed something because the narrator did not mention the exact location they were at in this scene, but the Congo and all neighboring countries were in turmoil during the African War.

When so many Congolese families were getting killed or trying to flee the country…this nice white American family was gloating away, speaking Kikongo with sellers at a local market.

On what planet were they on?!

Foreign language issues were distracting.

To add on: Some foreign languages used weren’t a good portrayal of how people spoke, especially if they lived in Kinshasa. Her children were going around saying “Sala Mbote”? I have never heard anyone greeting others saying: “sala mbote” and I grew up with Congolese parents. It would just be: “mbote.”

Maybe it’s just me though and it is a thing?

Conclusion

The book started super slow, but I was intrigued when it picked up at the 150 mark or so until the 300 pages or so. If the book had wrapped things up right around the time Mobutu came into power, post-colonialism, it would have made so much sense. Everything after that made no sense to me whatsoever.

I do appreciate the author writing about Congo and its history, and emphasizing the negative effects that Christianity may have had on the Congolese people; however, when I got to the end of the novel, I was angry and frustrated.

Maybe that was the point?